Tebbs Bend Battle, Kentucky

On July 4th, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln received word the Union Armies had won three decisive battles that auspicious day.

The biggest, most remembered, and honored battle was at Gettysburg, PA. This engagement, the Civil War’s defining one, was hard-fought for three exhausting days, July 1st to the fourth. A staggering number of men became casualties: over 7,000 killed, more than 33,000 wounded, and 11,000 missing. The site has become hallowed ground, now part of the U.S.A.’s National Monuments, millions of visitors drawn to this land every year. From that fateful event came Lincoln’s famous speech, the Gettysburg Address.

The second battle won that fateful day was the long, drawn-out combat in Vicksburg, MS. Continuously engaged for forty-seven days, from mid-May to early July, this conflict had numerous civilians fleeing their destroyed or confiscated homes to live in caves dug into the hillsides. When the food was gone, starvation and disease set in. Family pets, rodents, and reptiles were consumed. With the surrender, bitterness consumed Vicksburg. The 4th of July was not acknowledged or celebrated for more than eighty years in Vicksburg. But this crucial victory gave the Union control of the entire Mississippi River, guaranteeing supplies could navigate the river’s length, hopefully shortening the war.

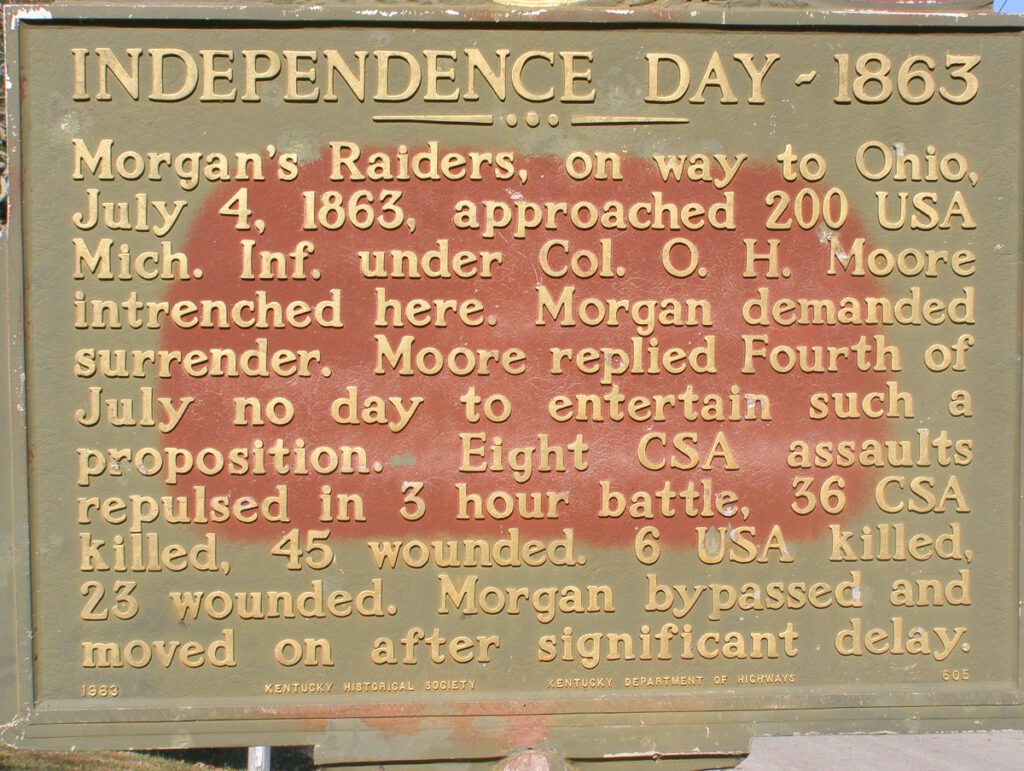

The third, and smallest battle, was a nasty skirmish at Tebbs Bend, Kentucky. According to Lincoln, this clash was considered ”one of the most outstanding small victories in the Civil War.”

Historian John Ramage stated, “It was unusual for a small Union force to resist Morgan, and to fight so fiercely and effectively.”

Tebbs Bend is not a town, but a rural area shaped by a horseshoe-type curve in the Green River. This arch winds through steep, wooded bluffs overlooking idyllic farmland near the Green River Lakes outside Campbellsville, in central Kentucky.

The battle of Tebbs Bend was a duel between the famed Confederate Cavalry Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan and Union Colonel Orlando H. Moore. Comparable to David and Goliath.

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (1825-1864) was a dashing, but conflicted man. He was born in Huntsville, AL, the oldest of ten children. The family moved to the Lexington, Kentucky area and began farming. Morgan began riding in his early years, becoming an excellent equestrian.

He always desired a military career, but the small size of the U.S. military offered only limited opportunities. That was about to change.

He attended Translyvania University in Lexington for two years but was asked to leave after dueling with another classmate. This would be Morgan’s pattern, very disciplined, showing great leadership and promise, then losing control, both of himself and the situation. There were continual trust issues with John Hunt Morgan.

Orlando Hurley Moore

Colonel Orlando Hurley Moore (1827-1890), on the other hand, was a very loyal and trusted leader. His decisive win at Tebbs Bend on July 4th, 1863, catapulted him into an elite group of heroes. Every newspaper and reference hailed him as “the man who saved Louisville.”

Orlando Moore was a native of the Kalamazoo, MI area. A multi-talented man, Moore made his living pre-war as a portrait painter and musician. A natural leader, he trained his horses to respond to different bugle commands. Originally posted to the Bay area in California, Moore is credited with keeping the West from seceding, as the South was trying to do. Wishing to be amid battles, not in a western outpost, Moore asked for and received a transfer east.

Sympathetic to the plight of the Black people, Moore wrote letters of protest regarding their treatment, especially of those who were serving as assistants to Union officers. Those Black assistants were often seized and forcibly taken somewhere in the South. These letters lead to two court martials from bogus charges, costing Moore a promotion to General. President Lincoln intervened, saving Moore’s military career.

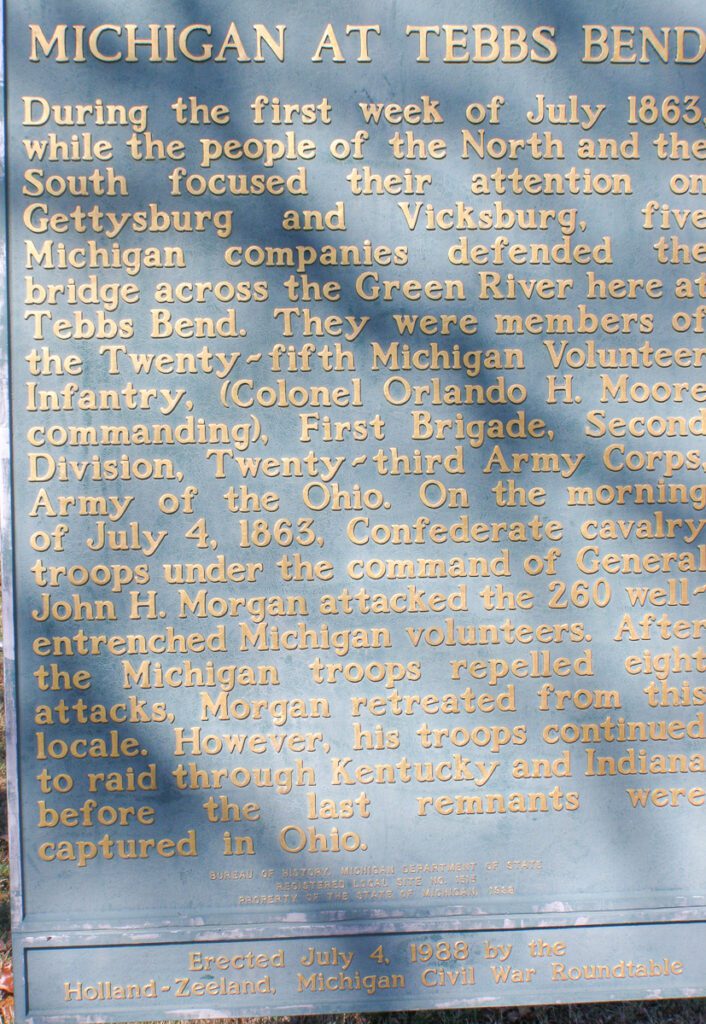

Back in action, Moore was given a small number (263) of raw, untested Michigan recruits – the 25th Michigan Infantry — and sent to Kentucky.

The Battle of Tebbs Bend

This was a battle that was not supposed to, and never should have, happened. It took place by a strange accident.

Confederate Cavalry Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan had spent the spring and early summer of 1863 foraging and skirmishing in Tennessee. In truth, he was not involved in any major conflicts during that time and was thought to be hungry for action. In retrospect, Morgan may have been jealous of another brilliant cavalry General, J.E.B. Stewart, who rode with and scouted for General Robert E. Lee, receiving continual accolades.

Mid-June, Morgan and 2,460 cavalrymen left Sparta, TN, heading north to Kentucky. His intention was to cut off the Union Army of the Ohio from the Confederates there. Another announcement was that Morgan intended to capture Louisville, causing great stress and panic in that town.

What is not clear is whether Morgan had any permission from his superiors, or if he was acting on his own. In any case, Louisville became alarmed and began devising methods to defend the city.

On July 2nd, Morgan and company crossed the Cumberland River, continuing their journey north. They camped that evening in the Cane Valley, between the cities of Columbia and Campbellsville.

The plan was to cross the Green River at Tebbs Bend on the fourth.

While the Confederates were resting in Cane Valley, scouts from the 25th Michigan prowled the countryside. In no time, they had discovered the campfires, tents, and horses of Morgans enormous cavalry and reported back to Moore. The Union soldiers began to fortify, fearing they would face a fierce group the following day.

Moore’s first order was to fell trees, making the charge up the steep bluff difficult, if not impossible. Axes rang all night, disturbing but not alarming, the local farm families. In key spots, Moore’s men erected abitisses, or lines of defense, which are interlaced rows of cut trees, their sharpened branches facing the enemy. Other trees, both removed and left upright, were used for rifle pit defense and the sharpshooters. Moore had battle experience in both the West and at Munfordville. He understood fortification was key.

Morgan’s men heard the all-night sound of axes. The usual scouts, Quick and Cassell, were recovering from wounds; a newer scout, Tom Frank, was dispatched. He discovered Moore’s position and reported there were only a small number of enemies. He did not, apparently, report the terrain and the steepness of the bluffs. Therefore, Morgan was not concerned.

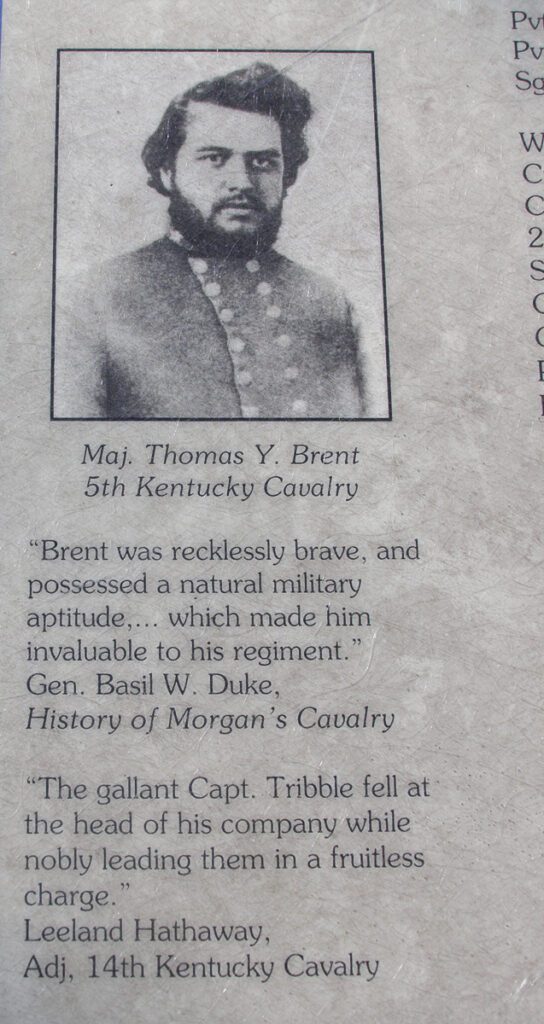

At sunrise, Morgan’s 2,400 plus company divided. Half were sent to flank Moore’s garrison and cut off their path of retreat. The other half walked into hell.

Union pickets fired first. Morgan’s artillery came alive, wounding two of the Michigan men hunkered in the rifle pit. Moore’s sharpshooters responded, killing, or disabling several of the cannon operators. From then on, the fight was a charge for the Confederates, straight up an unclimbable bluff, at times hand-to-hand combat. The 25th Michigan repelled them every time.

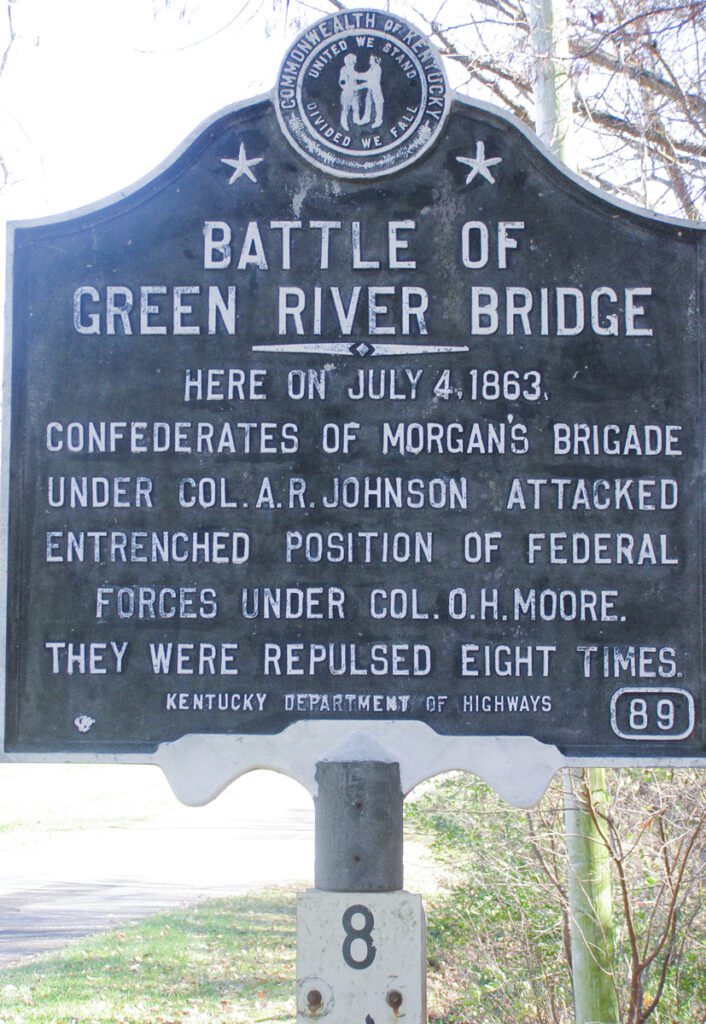

In the four-hour battle, Morgan’s men charged eight times. Eight times, they were driven back. About 7:00 a.m., Morgan called a cease-fire, sending three officers with a flag of truce. In a letter the officers sent to Moore was Morgan’s demand the 25th surrender.

Moore’s response, “This being the Fourth of July, I cannot entertain the proposition to surrender. I have a duty to perform for my country.” He resumed fire, ordering the newly issued British Enfield .577 rifles to take out the remaining cannons. They did.

Morgan’s men were instructed to charge, but climbing the river banks, with rifles and equipment was impossible. Badly exposed, the men were quickly shot down. The Confederates retreated, leaving dead, and wounded where they lay. Adding to the confusion, Moore used bugle signals inferring reinforcements were near, although that was not true. The nearest help for the Union soldiers was thirty or more miles away.

Another truce flag from the Confederates appeared, requesting time to aid the wounded and bury the dead in a mass grave. This request was granted.

Morgan lost thirty-five men that day, including twenty-two officers and all the skilled cannon operators. Another forty-five were wounded. All for a battle that never needed to be fought.

The Union side counted six dead and twenty-four wounded.

Morgan, out of respect for Moore, wrote the Union leader a complimentary note. Colonel Alston, Morgan’s Chief of Staff, wrote in his diary of Moore: “The colonel is a gallant man, and the entire arrangement of his defense entitles him to the highest credit for military skill. We would mark such a man in our army for promotion.”

Moore had been leading the 25th Michigan recruits for less than a year. They had not engaged in many, if any, skirmishes of hand-to-hand combat, like Tebbs Bend. They were new to battle, and they performed exactly as ordered. Later, commenting on the win, most agreed their faith and sense of patriotism fueled them. Soldiers stated they were “doing God’s duty.” Private John Wilterdink, a young recruit, wrote, “It is clearly seen that God fought for us. I see a higher hand in it because that is the first time John Morgan’s been beaten so badly.” Another soldier, Van Lente, “thanked God for delivering them from death.”

Louisville was sending praise, as Moore gave the city an extra thirty hours to prepare for Morgan’s assault. Although the Confederates battled the following day in Lebanon, KY, he never attacked Louisville.

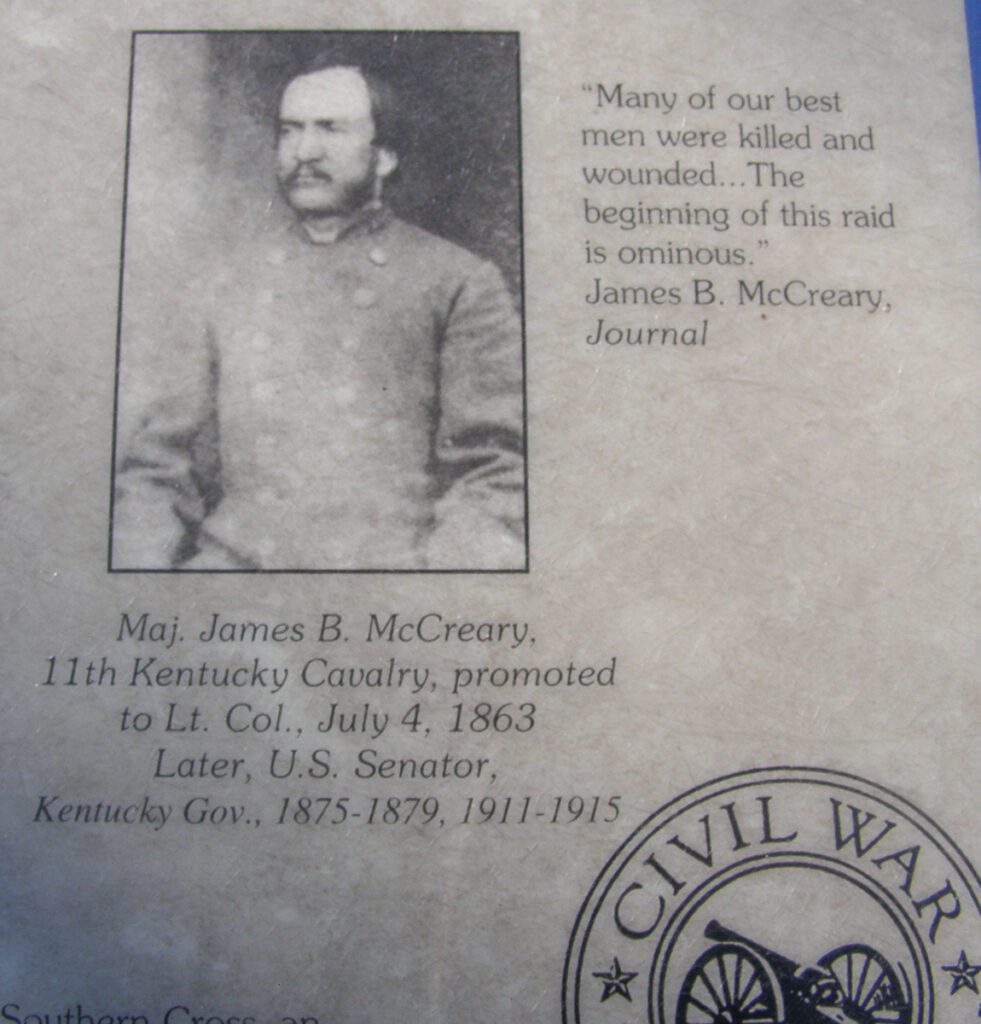

Aftermath for Morgan

Morgan was beaten badly. This defeat was noticed throughout all levels of the Confederate army, reinforcing the distrust officers had in him. Morgan continued raiding both Kentucky and Ohio, burning fields, capturing soldiers, and spreading terror for another year. He had great victories, but not all those battles were authorized or approved by superiors.

In June 1864, Morgan was assigned to a group of men that were young and inexperienced. His plan was another thousand-mile raid of Kentucky and Ohio. This time, he was under strict orders, by Braxton Bragg, not to cross the Ohio River. Those orders were disobeyed. He continued his legendary “Morgan’s Raid” with the newer recruits, venturing into territories he was ordered not to, all the while gaining no real advantage for the Confederacy. For this, he was demoted to leading only minor maneuvers.

With his trust at an all-time low, rumors began circulating that Morgan should be investigated on possible criminal banditry charges. This was too much for Bragg. Morgan was relieved of his command.

Even that did not stop John Hunt Morgan. He began a plan to raid Knoxville, TN.

Morgan and his green recruits arrived in Greeneville, TN in early September 1864. There, a young child recognized him and made his way to the Union cavalry camp nearby, reporting Morgan’s location. The Union forces decided to take immediate action.

A tremendous lightening storm that night helped the Union in two ways. It kept Morgan’s scouts in their tents and lit the way for the Union on the unfamiliar roads. Before morning, Morgan was captured.

Trying to escape, Morgan was shot in the back, piercing his heart, resulting in instant death. He is buried in Lexington Cemetery.

After Morgan’s death, his obituary appeared in the Chicago Tribune, September 15, 1864:

Was Morgan a Gentleman?

An answer from Parson Brownlow

Jeff. Davis’ organ in this city says, “Morgan, with all this faults, was an honorable foe and in private life a gentleman.”

Now hear Parson Brownlow, who knew John Morgan, although probably not so friendly to him as the Times:

John Morgan is no more! And when he died, a thief and coward expired! He was killed in Mrs. Williams’ back yard, or cabbage patch, stalking from danger. He was shot through the heart by Andrew Campbell of Co. G, 13th Tennessee Cavalry, while trying to escape. There should be a salute fired in front of every horse stable in the land in honor of his death! And all fine horses and mules should be notified that they may now response in quiet at night, and graze in peace in the day time.

Morgan leaves a large amount of gold and greenbacks, cotton and real estate, the proceeds of his thieving exploits, resulting from untold murders and robberies, through a spree of three years. Who his legal heir is will be difficult to settle. His first wife was the sister of Col. Bruce of Kentucky. She died in Lexington from neglect and bad treatment of her debased, gambling, and thieving husband. His second wife was the negro wench he had with him during his residence in this city. She is in Kentucky. His third wife is the daughter of Chas Ready, of Murfreesboro, and she is at Abingdon, in Virginia. Our own opinion is, that the negro wench has the oldest claim upon his estate, but we leave this grave question of law to be settled in the Confederate Courts, or by special acts of their Congress.

Gen. Gilliam is in our town, and brought with him eighty-six of Morgan’s men, on Monday evening, who we saw turned over to the jail we were once an inmate of. Some of them were barefooted, and bare-headed and bare-backed. All looked dirty and mean as though they were fit subjects to be commanded by a common horse thief.

Capt. Withers of Covington, A.A.G., Capt. Clay of Lexington, son of Thos. H. Clay and three others of Morgan’s staff are among the prisoners. Young Clay is pretending to be sick, so as to cheat our authorities in the paroling of him to the privilege of the town.

We are informed that the members of Morgan’s staff were captured in a “potato hole” in a back yard in Greenville — a sort of place where potatoes and cabbages have been buried. Gallant knights, these.”

Aftermath for Moore

Moore was promoted to brevet major for “gallant and meritorious service at Tebbs Bend.” He fought bravely for the rest of the Civil War, seeing action in the battle of Franklin and being part of the capture of Fort Anderson in February 1865.

He remained in the regular Army after the end of the Civil War, being assigned to the South, overseeing reconstruction. Due to Native American uprisings and his knowledge of the West, Moore was quickly reassigned to California.

Because of his kind nature, Moore found peaceful ways, not military force, to keep the Natives in check. “ Possessing honesty and keenness of skill in the arguments he made use of, as to not only convince the redmen of the foolishness of their purposes when restive for the warpath, but at the same time gaining their friendship and confidence,” came from an unnamed quote.

While on duty in the Rocky Mountains in the summer of 1880, Moore suffered a sunstroke, causing him to fall from his horse and remain unconscious for eleven days. Although he recovered, he was never the same, eventually asking to be relieved of his duty.

Moore died in 1890 and is buried beside his wife in Tulare, CA.

Tebbs Bend Today

Tebbs Bend is still a quiet, peaceful area, very much worth a visit. The battle site is spread along a three-mile road trip, which encompasses twelve battle site related stops. The tour is open year-round.

Stopping first at the Toll Gate House is recommended. Here, a small museum is located, with maps of the route, photographs, and history of the area, both before, during and after the battle.

Seven miles of hiking trails line the Green River Nature Trails. Right behind the Toll House is one of the trailheads. The other is located on a nearby historical farm. The trails are beautiful, full of birds, wildlife, and views of the river.

The Green River and the Green River Lakes area still feel untouched and natural. Certainly, the river has changed course since 1863, the bluffs not as steep, but time spent here will propel you back in time, giving a sense of the great Civil War.